Keynes' presumption

His reliance on statesmen being rational while he was young.

Practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.

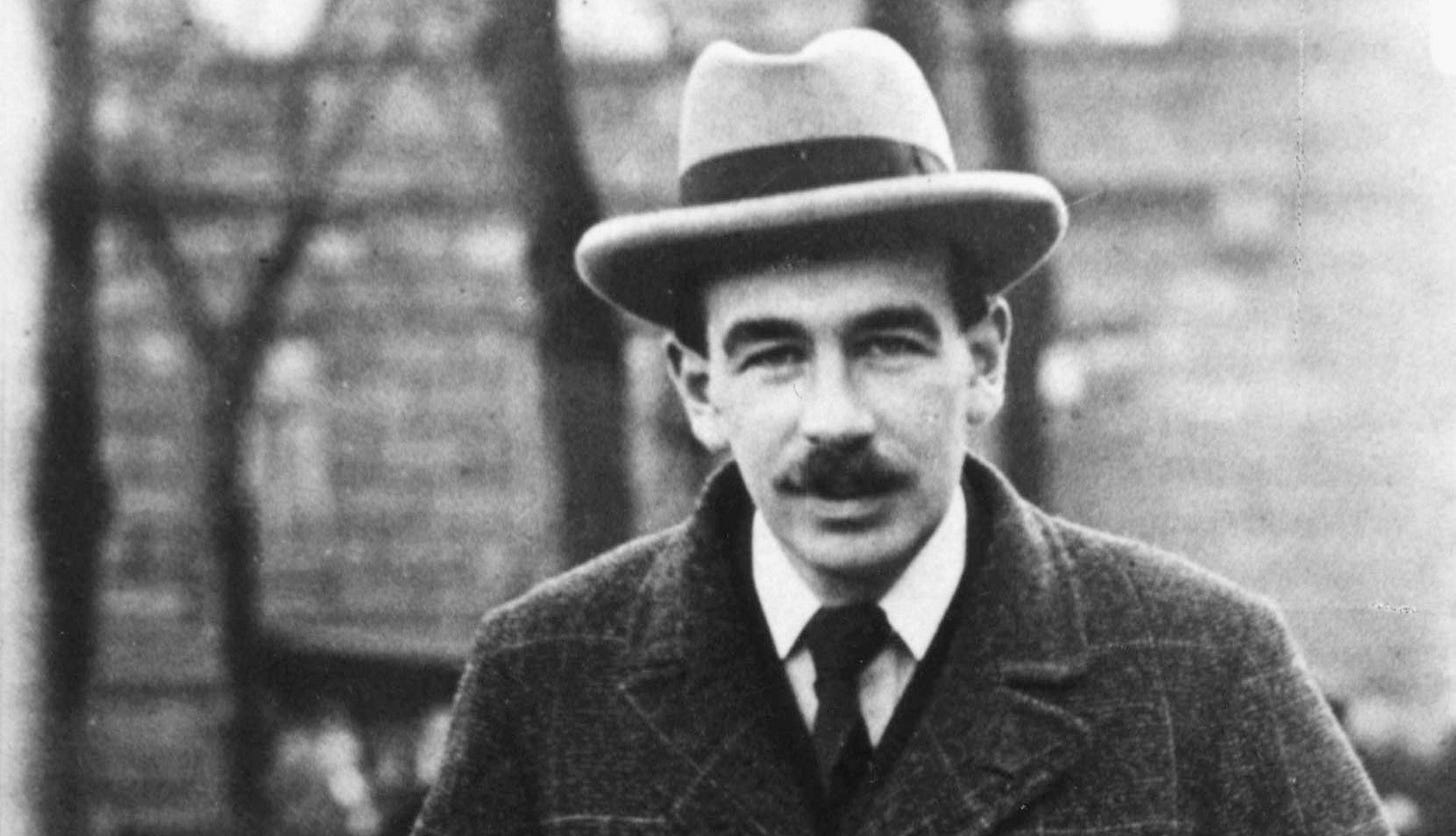

Probably the best-known of the millions of words which John Maynard Keynes wrote, they capture weariness with the political world in which he had been involved with decades.

To understand how he came to write them, it’s useful to go back to the first weekend of August 1914. As Britain teetered on the brink of war, the Treasury was desperately trying to avert a currency crisis.

With London, the hub of international finance, banks were panicking about their exposure to organisations in what were about to become enemy states. Seeking to secure their own positions, they were considering delivering bank notes to the Bank of England and demanding repayment from the bank’s gold reserves.

Keynes was barely 30, but he had already established himself as a brilliant monetary economist, who could move easily between academic debate at Cambridge and advising policy makers in Whitehall and Westminster. Summoned to the Treasury to share his opinions, he dashed there from Cambridge, riding pillion on his brother-in-law’s motorbike.

Within a week, the government’s willingness to provide the necessary liquidity to the markets had defused the banks’ threats. While Keynes was largely an interested bystander in the process, providing some useful insights, he was able to take the notes which he would turn into journal papers by the end of the year.

That week, Keynes discovered the excitement of wartime decision making. His return to Cambridge, where classes were almost emptied because so many students had enlisted in the armed forces, was brief, Within a year he was back in the Treasury within a year, taking on an advisory role and working closely with senior politicians.

Already active within the Liberal Party for a decade, he quickly became a friend of government ministers, including the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith. He accepted their arguments that war had regrettably become necessary to preserve an international order based on agreement among nations.

Nominally a pacifist, Keynes drafted a statement of conscientious objection before the introduction of conscription. It turned out not to be necessary because by Keynes quickly reached a high enough rank within the Treasury to be exempt from service.

Keynes’ pacifist friends in the Bloomsbury Group repeatedly urged him to resign from the role in which he secured the financing of Britain’s European allies.

As the fighting continued, his friend Asquith was replaced as Prime Minister by Lloyd George. Keynes despised his ability to tell politically expedient stories to keep power, and his willingness to spend money for that purpose.

Through the war, Keynes clung fast to his hope that at its end, there would be a just peace.

In November 1918, the guns fell silent and the fighting stopped. Lloyd George called an immediate General Election, promising a “land fit for heroes” and that “Germany must pay”. His resounding victory gave him a strong mandate to negotiate at the Paris Peace Conference.

Very quickly Keynes discovered the extent of his presumption. The would be no just peace.

The European allies - Britain, France and Italy - agreed that the Central Powers, especially Germany and Austria, should shoulder the whole burden of the war. Only the American President, Woodrow Wilson, seemed willing to exercise some restraint.

However, Wilson was most interested in achieving a political settlement based on recognition of Europe’s nations, with their continuing peace guaranteed by a permanent League of Nations. To achieve that, he was willing to tolerate the French and British demands for huge reparations.

That appalled Keynes. By day, he dedicated himself to serving the interests of a government which - in his evening conversations - he could not support.

His presumption continued. He hoped that he could change the direction of the Peace Conference’s negotiations, simply through force of logic. As a middle ranking civil servant, it was a heroic, futile effort. The statesmen gathered in Paris had committed themselves irrevocably to the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.

So, in June 1919, on his 36th birthday, he resigned from the Treasury.

It should, perhaps have been the end of his career. Instead, over the next 15 years, he would return repeatedly to public debates, experiencing repeated defeats until with The General Theory, he finally had strong enough arguments, even for political leaders to listen to him.

It had taken a long time, but he would not have to rely on posthumous influence for his political influence to be felt.